Mapping Intelligence: From AI Transformers to Brain Waves and Beyond

How Sejnowski’s Journey from ICA to Long-Term Working Memory Illuminates a New Roadmap for Far-Transfer Brain Training for IQ

1. A Visionary Mentor - Revisited

I can still picture myself as a 20-year-old undergrad in the UK, working my way through Terry Sejnowski’s 1997 paper on Infomax ICA.

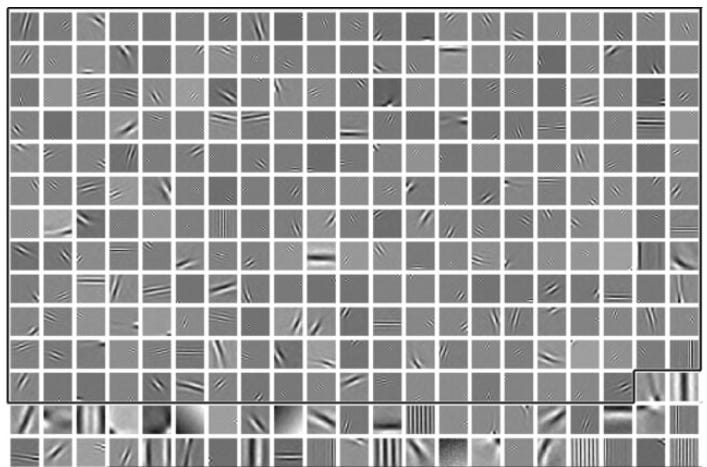

I’d been studying visual psychophysics and here was this bold idea: use independent component analysis (ICA) -- a way of untangling mixed signals -- to pull out V1-like edge detectors straight from raw photographs. V1 is the first cortical area for visual processing, and its cells are known to respond selectively to ‘edges’ in small regions of the visual image.

I remember thinking, “This is very important - but do I understand it?!”

It turns out the same ICA learning rule could later ‘unmix’ noisy EEG recordings into clean neural rhythms (like alpha, theta, delta) or separate fMRI scans into distinct brain networks -- all without ever being told what the ‘right answer’ was. Little did I know then that Terry’s elegant, information-maximising insights would become a connecting thread in my own work, guiding me from those first experiments in vision science to today’s frontier of AI-inspired theories of memory and intelligence.

Fast-forward to today, and Terry Sejnowski is at it again -- this time borrowing from AI’s transformer models (a class of neural networks that process sequences by learning which parts ‘attend’ to each other) to propose a neurobiological model of long-term working memory.

Long Term Working Memory: The brain’s system for holding and manipulating information over hours rather than seconds.In his latest Substack piece, he draws an elegant analogy: just as transformers spatialise word sequences via positional encodings (embeddings that tag each word’s place in a sentence) and attention (weighting how strongly each word influences every other), the cortex may convert events unfolding over time into dynamic maps (transient patterns of neural activity laid out across brain regions) through traveling waves (ripples of neural oscillations that sweep across tissue) and spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP).

STDP: a rule where synapses strengthen or weaken based on the precise timing of neuronal spikes.In this educational article, I’ll build on Terry’s two decades of insights -- from ICA’s statistical uncovering of receptive fields to transformer-inspired cortical dynamics -- by focusing on hippocampal–prefrontal cognitive maps which is the core hub of intelligence on my understanding.

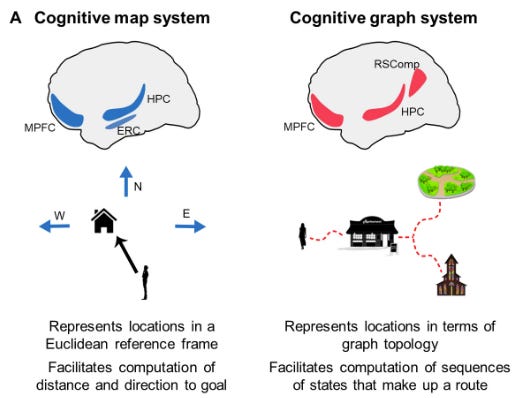

2. Cognitive Maps: The Hub of IQ

Cognitive maps are the true engine of far-transfer brain training - training that improves broad cognitive abilities, not just the practiced task. I will show how blending AI architectures with map-based neuroscience points the way to truly enhancing human intelligence by harnessing the power of these maps. When I talk about building and training cognitive maps, I am talking about training a single, dynamic mapping system centered in hippocampus and PFC — that originally evolved for precise navigation and flexible route planning in physical space, but has since been co-opted to chart conceptual ‘spaces.’ These neural maps form the substrate of long-term working memory, powering problem solving, decision making, and learning (IQ).

3. Sejnowski’s Transformer Analogy for Temporal Context

At its core, a transformer is an AI model that processes sequences -- like words in a sentence -- by learning which elements to ‘attend’ to when predicting what comes next.

Technically speaking, rather than reading one word at a time, transformers build a giant spatial embedding (a fixed-length vector that encodes every item’s position and content) so the network can consider the full history of inputs simultaneously. Positional encodings tag each item’s place in the sequence, and attention scores weight how strongly one element influences another. This lets the model maintain context across dozens or even hundreds of words without relying on slow, step-by-step recurrence.

Sejnowski argues that the brain achieves something similar -- only dynamically. Instead of stuffing every past input into one big vector, the cortex may use traveling waves (ripples of neural firing that sweep across tissue in milliseconds) to replay recent events in space. At the same time, spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) tweaks synaptic strengths based on the precise millisecond timing of neuron spikes, temporarily ‘writing’ these wave-driven patterns into transient circuits. Together, waves plus STDP could recode a stream of experiences into a spatial map distributed across cortical areas - that is a cognitive map that gives us a mental model of where we are and where we could go from here in any domain.

Let’s make this a bit clearer!

4. Dynamic vs. Static Maps: From Transformers to Traveling Waves

Imagine you’re reading a book and you highlight every important sentence in one go — then you never change those highlights unless you start over. That’s how a transformer works: once it processes a sentence, it builds a fixed snapshot of what matters (which words relate to which), and it only updates that picture if you feed it the whole sentence again.

Your brain, on the other hand, writes and rewrites its own highlights on the fly:

Traveling waves are like a spotlight sweeping across a stage of neurons. Each wave briefly lights up the cells that represent the last few moments of experience.

Spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) is the ink that those waves use: whenever two neurons fire almost together, their connection gets a little stronger; miss the timing, and it fades again.

Every few milliseconds, a new wave passes through, updating which connections are highlighted. Old highlights fade, and new ones appear — so your brain keeps a rolling record of the recent past without ever freezing it in place.

Think of it as a palimpsest: an ancient manuscript that’s scraped clean and reused, yet still carries faint traces of what was there before. Your cortex does the same, constantly overwriting and refreshing its map of where you’ve been and where you might go next.

In this way, the hippocampal–prefrontal system acts like a living transformer — never stuck in one static view, but dynamically updating its mental map with every new ripple of thought and wave of memory.

This dynamic updating is exactly what underpins the cognitive maps we use for problem solving. By continually refreshing which ideas and memories are most strongly linked, the brain creates a live ‘map’ of concepts and their relationships. As you tackle a complex puzzle or plan out a project, those shifting highlights guide you from one concept to the next — linking past knowledge with fresh insights, steering you through abstract spaces just as surely as a GPS guides you through a city. This flexible, ever-rewritable map is what lets us adapt on the fly, combine ideas in novel ways, and arrive at creative solutions that a static snapshot alone could never uncover.

5. Trident G Theory: Maps as the Engine of Far-Transfer

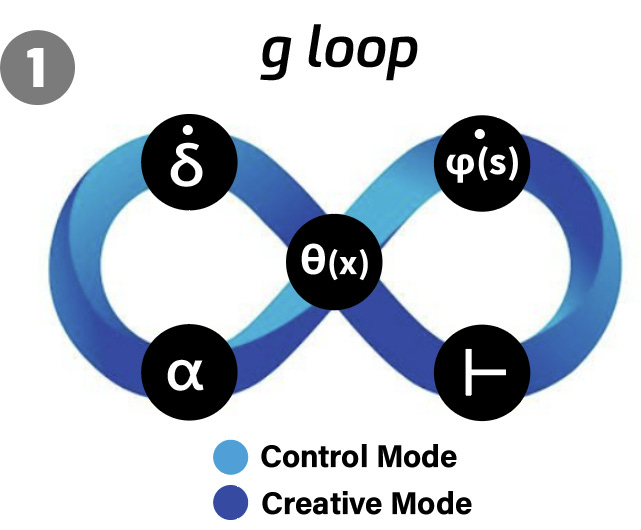

So far we’ve seen how the brain writes and rewrites its own cognitive maps on the fly. But what decides when those maps get updated and by how much? That’s the job of the Trident G g loop , a self-correcting control circuit that turns every surprise into better predictions.

Prediction Error (δ)

Every unexpected outcome - like a lighter-than-expected coffee mug or a surprising plot twist - generates a prediction error, δ, the gap between expectation and reality. This signal, carried by phasic dopamine bursts to hippocampus and PFC, flags “Hey, pay attention!”Dynamic Learning Rate (α)

Not every δ should trigger a full map overhaul. The brain uses α as its “volume knob” on learning:When δ is large and the world seems volatile, α rises, pushing us into Creative Mode - rapidly reshaping our maps to explore new possibilities.

When δ is small or the environment is stable, α falls, shifting us into Control Mode - consolidating existing maps and avoiding needless rewrites.

Decision Threshold (θ)

Finally, θ gates whether we explore (engage fluid reasoning) or exploit (lean on crystallised skills). Big, reliable errors lower θ (opening the door to exploration), while minor or inconsistent errors keep θ high (favoring known strategies).

All three — δ, α, θ — operate on your mental model φ(s), the hippocampal–PFC map itself. Each loop uses δ to decide if and how much to adjust φ(s), then θ to choose whether to test those adjustments in novel ways or stick with familiar routes.

Why the g loop drives far-transfer

Because it constantly calibrates when and how our maps adapt, the g loop ensures learning stays both flexible and stable. Early on, high α and low θ spur broad exploration—discovering new connections across ideas. As patterns solidify, α drops and θ rises, cementing those maps into reliable strategies. This dance of surprise and consolidation is what lets you apply lessons from one domain to another—whether you’re mastering a dual n-back game or tackling a novel work problem, your hippocampal–PFC maps (and the g loop that shapes them) are the engine behind genuine far-transfer.

Linking the g Loop to Long-Term Working Memory

Sejnowski’s model of long-term working memory proposes that traveling waves and STDP extend our moment-to-moment maps out over minutes to hours by repeatedly rehearsing sequences and transiently strengthening the very synapses that carry those maps. The g loop sits atop this machinery: each prediction error (δ) not only tweaks the map via STDP — the “ink” of short-term weight changes — but through α and θ determines how often and how deeply those wave-driven rehearsals are replayed and consolidated into longer-lasting working-memory traces. In other words, the g loop’s dynamic learning rate sets the pace for STDP-mediated rehearsal, while its decision threshold gates when those rehearsals transition information from fleeting activity packets into durable, map-like circuits — exactly the process Sejnowski argues underlies our ability to hold context across hours.

6. Implications for Brain Training: Encoding Relations and Building Complex Cognitive Maps

Building on the g loop’s role in shaping dynamic hippocampal–PFC maps, we can design training that explicitly targets both relational encoding and map consolidation.

Relational n-Backs

Traditional n-back games simply flag when an item (say, a blue square) repeats n steps later — hardly demanding you encode the relationship between the past and present. By contrast, episodic relational n-back mixes in novel colored shapes and asks you not just to spot repeats but to recall how each stimulus dimension (colour, shape, size) is related over time. This extra step of binding color, shape, and temporal order taps directly into hippocampal time cells (which fire in sequence to mark each moment) and successor representations (which predict likely future states). In real time, your brain weaves together when and what, forging richer, multi-feature linkages.

Map Consolidation

Encoding those fleeting relations is only half the battle. To achieve true far-transfer, you must stitch them into durable, multi-dimensional maps by moving them out of your few-second short-term working memory and into long-term working memory, where STDP-driven rehearsals replay and solidify the patterns over minutes to hours. In practice, this means alternating bursts of high-α relational encoding (Creative Mode) with low-α consolidation phases (Control Mode), letting your hippocampal–PFC circuitry prune noise and reinforce the strongest relational pathways.

By combining relational n-back’s binding demands with staged consolidation, you end up with robust cognitive maps — networks of concepts linked in time and feature space — that serve as the substrate for flexible thinking, problem solving, and genuine far-transfer across domains.

7. Conclusion

We’ve traced a remarkable lineage — from Terry Sejnowski’s early Infomax ICA uncovering ‘edge detectors’ in vision, through transformer-inspired traveling-wave dynamics, to the g loop’s self-correcting updates of hippocampal–PFC cognitive maps. This integrated framework shows that the same circuits once evolved for physical navigation now underlie our ability to chart abstract problem spaces — holding context for hours, flexibly binding relations, and guiding creative exploration or stable exploitation as needed.

Future Directions

Intervention Trials:

Randomised controlled experiments comparing traditional n-back versus episodic relational n-back, measuring far-transfer effects on fluid reasoning, planning and learning.

NeuroFlex App Prototype: An AI-driven platform that uses real-time performance and biofeedback (pupil, heart-rate variability) to tune α and θ — maximising engagement of the g loop for each learner.

Cross-Domain Applications:

Extending map-based training to language learning, creative problem solving, and real-world decision making — testing whether training the neurobiology of cognitive maps accelerate and deepen skill acquisition in diverse fields.

By uniting the computational power of AI architectures with the brain’s dynamic mapping machinery, I believe we stand on the brink of a new era in cognitive enhancement — one where training doesn’t just improve narrow skills but fundamentally reshapes the maps that underlie human intelligence.