The Breakthroughs You Don’t Keep! (But Could)

From Temporary Capacity to Permanent Cognitive Skill

Why good sessions don’t always turn into lasting skill, and a 90-second habit that makes your best moments transferable

The moment it vanishes

You’re in a practice session, writing, coding, problem-solving, training with IQ Mindware, whatever. You’re grinding away, slightly stuck, and then something clicks.

Not as a vague “I get it”, but as a clean ‘move’. The whole situation suddenly has a shape. You can feel the right next step - a new strategy or method manifests. You execute it, things flow, and you finish the session with that quiet satisfaction: progress.

Then a few days later you’re back in a similar spot and… it’s not there.

You remember that you solved this kind of thing recently. You remember there was a key idea. But the move itself, the thing you could actually do, has evaporated. You end up re-learning the same lesson instead of building forward.

That isn’t a motivation problem. It’s a capture problem.

Two kinds of learning you’re doing (often without realising)

When you improve, you’re usually doing two different kinds of learning at once.

First, there’s smoothing: you’re getting more fluent at what you already do. The same approach, fewer errors, less effort. This type of learning often sticks pretty well, especially inside the same setting.

Second, there’s restructuring: a genuinely new way of seeing the task, a better sequence, a different rule of thumb, a new move. This can arrive as a clear “aha”, but it also often happens quietly - without conscious recognition. You just notice, later, that you’re better.

In Trident G language, restructuring is the birth of a new operator, a move, inference, strategy you can re-use. The catch is that new operators are often born tied to the moment and the ‘wrapper’ - the specific task context. If you don’t make them portable, they can stay context-bound, which looks like “I lost it”.

So no, most learning isn’t lost. Much of it accumulates as steady refinement. But the specific upgrades that would save you time in other contexts are the ones most likely to leak away if you never pin them down.

Why breakthroughs vanish

Three forces work against you.

State lock. Breakthroughs often happen when you’re unusually ‘online’: high focus, clear goals, the right amount of pressure, the right path dependencies. Later, when you’re back to baseline, the pathway back to that move isn’t as available.

Context glue. The new move gets tangled up with the surface features of how you found it: this exact problem type, this tool, this sequence of steps. It works there, so your brain treats it as ‘local’.

Old habits win under load. Your previous approach has deep grooves. When you’re tired, rushed, or emotionally disrupted, you revert. Without a crisp distinction between the new move and the old near-misses, you slide back to automatic defaults.

Put those together and you get a familiar pattern: “I figured it out once” becomes a memory, not a transferable cognitive skill that you can apply more broadly.

The fix: turn capacity into a portable move

When the new move appears, you don’t need a long journal entry. You need a fast conversion: take what you just did and turn it into something you can retrieve later, in a different ‘wrapper’ - a different task, a different context. Ensure you can reapply it creatively even.

I call this spike-capture. The rule for this is: when the click happens, pause for 90 seconds.

The 90-second spike-capture protocol

Step 1: Spot the spike

Look for the signature: effort suddenly drops, uncertainty collapses, and you can do something you couldn’t do five minutes ago. When you feel that, don’t rush forward. Stop.

Step 2: Name the ‘move’ (15 seconds)

Complete this sentence, out loud or in writing:

“The move is: ___ instead of ___.”

Make it behavioural. Something you could watch yourself do. The contrast matters because it stops the idea turning into a vague motto.

Examples:

“The move is: write the claim first, then support it, instead of trying to do both at once.”

“The move is: check the exit condition before the loop, instead of assuming it’s handled inside.”

“The move is: name the feeling first, then explore causes, instead of jumping straight to fixing.”

Step 3: List two lookalikes (45 seconds)

Write two near-misses, things that feel similar but aren’t it:

Not: ___

Not: ___

Definitely: ___

This is the most underrated step. It’s what makes your brain distinguish the new move from the usual, tempting substitutes.

Example 1: Writing / argument

“The move is: state my claim in one sentence, then give one piece of evidence, instead of building a long lead-in and hoping the claim becomes obvious.”

Not: “Add more detail before I commit.”

Not: “Qualify everything so I can’t be wrong.”

Definitely: “One-sentence claim first, then one supporting reason/evidence.”

Example 2: Problem-solving / planning

“The move is: write the constraints first, then generate options against them, instead of generating options in my head and checking constraints afterwards.”

Not: “Make a longer to-do list.”

Not: “Try to remember all constraints while brainstorming.”

Definitely: “Externalise constraints, then search for options that satisfy them.”

Step 4: Install one cue (30 seconds)

Create a simple trigger:

“When ___, then I will ___.”

Examples:

“When I feel the urge to justify while claiming, then I will anchor the claim first.”

“When the code path feels messy, then I will check the exit condition before I refactor.”

“When someone is distressed, then I will name the emotion before I problem-solve.”

That one line creates a retrieval path you can use in real life. You’re no longer relying on inspiration.

What about improvements you don’t notice?

Here’san interesting twist: a lot of genuine upgrades don’t arrive with conscious insight.

Learning research shows that people’s improvement often happens in segments: a stretch of gradual gains, then a jump, then another stretch, as if you quietly switched to a better approach without announcing it to yourself (Donner & Hardy, 2015 - see the Appendix).

In Trident G terms, those are still restructuring events. They’re just stealth. If you only capture what feels dramatic, you miss the bulk of your real changes.

So you need a second capture mode: retrospective capture.

Retrospective capture: harvest stealth improvements

Once a week (or after a block of sessions), spend 10–15 minutes doing this:

1) Find the inflection

Look at your last few attempts. Where did things start to feel easier or cleaner? What changed in the outputs?

2) Do a quick wrapper/context swap

Try the same skill in a deliberately different format or setting. If you learned something while writing, try speaking. If you improved in one task type, try a cousin task. If it holds up, you’ve probably got something portable. If it collapses, it may be local refinement, which is still useful, just not yet transferable.

3) Reverse-engineer the move

Write:

“Before, I was ___.”

“Now, I’m ___.”

“The key difference is ___.”

“The move is: ___ instead of ___.”

Immediate capture is for felt “clicks”. Retrospective capture is for quiet upgrades. You want both.

Try this for a few days

Pick one domain you practise regularly, work, training, learning a tool, anything.

For the next seven days:

When you feel a click, pause and do the 90-second capture.

And sometime during the week, do a 10-minute retrospective harvest.

The goal isn’t to capture everything. The goal is to stop letting your best moments remain trapped inside the moment that created them.

If you do this consistently, you’ll notice the difference in a very specific way: you won’t just be “better in practice”. You’ll start catching yourself doing the move in the wild because the cue fires and the operator runs.

That’s when improvement stops feeling circular and starts feeling cumulative.

Reference: Donner, Y., & Hardy, J. L. (2015). Piecewise power laws in individual learning curves. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 22(5), 1308–1319. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-015-0811-x

Research Basis

The scientific foundation for spike-capture comes from recent work at Zhang’s Computational Neuroscience Lab showing that heavy-tailed learning dynamics emerge naturally from entropy-maximisation under relevance constraints (Zhang & Tang, 2025, PNAS). The Trident-G framework extends this to explain why some training produces portable/transferable skills and strategies while other training produces ‘thin automation’ - that doesn’t extend beyond practice gains on the task you’ve spending time on — even when both show improvement.

Appendix

Here is fascinating data from a learning study by Yoni Donner and Joseph Hardy (2015).

Incidentally, Yonnie has said this about my own cognitive intervention work:

I have seen many similar sites / companies, so to be honest I did not expect much in the beginning, but I am impressed – I like your approach and I think you are actually putting emphasis on exactly the interventions that work.

Reference: Donner, Y., & Hardy, J. L. (2015). Piecewise power laws in individual learning curves. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 22(5), 1308–1319. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-015-0811-x

You can see… your learning curve in these cognitive training exercises isn’t a smooth rise - it’s made of distinct chunks with sudden jumps between them, and those jumps mark the moments when you (often unconsciously) switched to a better strategy.

Reading the Figure: Four Different Tasks, Same Pattern

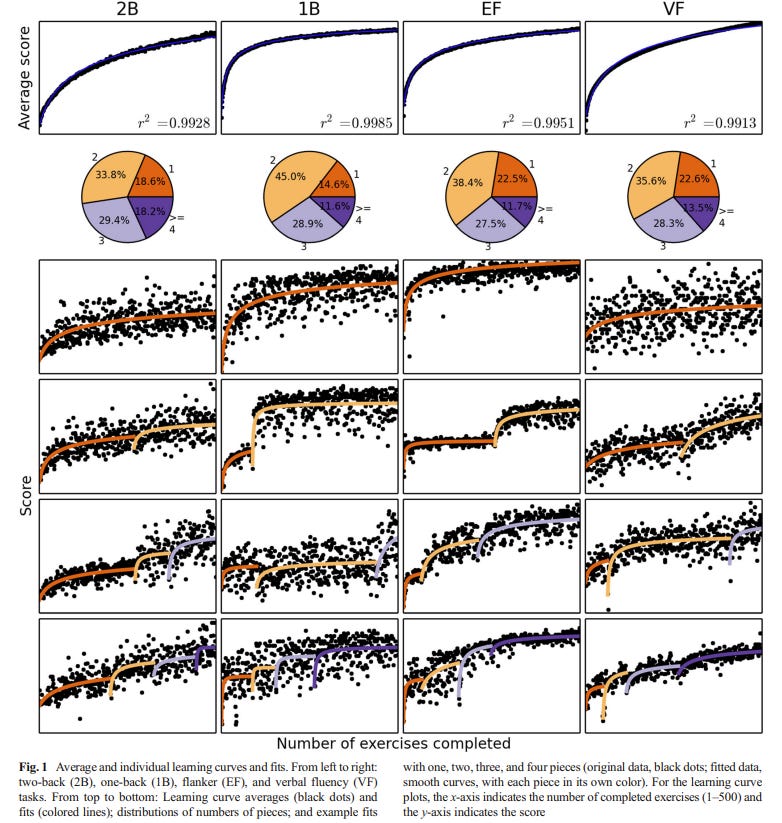

The figure shows learning curves from four different cognitive tasks, tracked across hundreds of practice attempts:

2B = Two-back working memory task (remember items from 2 steps ago)

1B = One-back working memory task (remember items from 1 step back)

EF = Executive function / flanker task (ignore distractions, respond to targets)

VF = Verbal fluency task (generate words under constraints)

Top row: Average curves look smooth—the usual story of “practice makes perfect.”

Middle rows (individual learners): The black dots are actual performance on each attempt. The colored lines show what the math found: 2-4 distinct “chunks” (orange, purple, blue segments) connected by sharp transition points.

Bottom row: More individual examples showing the same pattern — jumpy ‘piecewise’ chunks, not smooth curves. Let’s call them ‘pieces’ as this is in the title of the article:

What the “Pieces” Mean

Each colored segment represents a different strategy or approach:

Within a piece (smooth part):

You’re getting better with your current strategy

Gains are gradual and follow a power law (fast improvement early, slower gains later)

This is Type-1 learning in Trident G terms: tuning and stabilising the current program

At transition points (the jumps):

You (often unconsciously) switch to a qualitatively different strategy

Often there’s a brief dip or plateau right at the transition (visible in several curves)

Then performance takes off again on a new trajectory

This is Type-2 learning: installing a new operator

The pie charts show how many pieces each task typically had:

Most people had 2-4 strategy shifts across ~100-150 practice trials

The colors in the pie match the colored segments in the individual curves

Purple = first strategy, orange/blue = later strategies

There are individual differences though which is interesting.

Three Key Findings (And Why They Matter for Spike-Capture)

1. Strategy shifts are multiple, not unitary

Look at how many curves have 3-4 distinct pieces. You’re not having one ‘aha moment’ per skill — you’re having multiple reconfigurations as you learn. That means there are many opportunities for capture, not just one breakthrough.

2. You often don’t consciously notice them

The researchers didn’t ask participants “what’s your strategy?” They detected the shifts purely from the performance data — the change points where the curve’s slope suddenly changes. Most learners couldn’t articulate what changed, but the data found clear transitions.

This is why retrospective capture matters. You can’t rely on “I’ll know it when I feel it” because most reconfigurations happen below conscious awareness.

3. Later strategies are typically better

The orange and blue pieces (later strategies) typically reach higher asymptotes than the purple pieces (first strategy). The transitions aren’t random — they’re directional improvements. But without capture, you might slip back to an earlier, worse strategy under load or in a new context.

The Dip at Transitions (Look Closely)

In several individual curves (especially column 2, row 3), you can see performance actually drops briefly right at the transition point—then recovers and improves.

What’s happening: You’re abandoning a familiar-but-limited approach for a new-but-unfamiliar one. There’s a temporary destabilisation (in Trident G terms: an out-of-psi-band excursion) before the new program settles and starts outperforming the old one.

Why this matters: If you feel like you’re suddenly worse at something after trying a new approach, that’s often not regression — it’s a transition dip. The retrospective capture protocol helps you recognise this pattern: if performance rebounds and exceeds your previous best within a few sessions, you’ve likely made a genuine strategy shift worth capturing.

How This Grounds the Two Capture Methods

Immediate capture (felt breakthroughs):

Works for the subset of transitions that surface into awareness

You feel the ‘click’ right at the transition point

Rare but high-value when they occur

Retrospective capture (stealth shifts):

Works for the majority of transitions shown in this figure

You detect them by comparing performance across sessions

Find the inflection point where the curve’s character changes

Reverse-engineer what you’re doing differently in the new piece

The combination: Immediate capture for the 20-30% of shifts you notice; retrospective capture for the 70-80% you don’t. Something like that! Together, they ensure you’re not leaving the majority of your genuine learning events uncaptured.

Try This With Your Own Cognitive Training Data

If you track any kind of practice metric (accuracy, speed, error rate, completion time), you can look for this pattern yourself (for instance with the dual n-back app):

Check your last few session’s performance

Look for places where the slope changes, not just ups and downs

Ask: “What was I doing before vs after this point?”

If you find a clear shift, run retrospective capture even if you never felt an “aha”

The Donner findings suggest you may find 2-3 transitions in most skill-building arcs of practice sessions over e.g. 20-40 sessions. That’s 2-3 operators worth capturing, even if none of them felt like dramatic breakthroughs at the time.

The trick is to capture those strategies in a way that transfers outside of the context of the game. An effective way to to make this far transfer rather than game-locked improvement, is to write the operator in wrapper-free language: what’s the strategy or inference, and what’s the trigger? Then run a quick ‘wrapper swap’ test (different task or context, same underlying structure) so it compiles into something you can apply outside the original context.